The Construction Value Chain - Part II : Cash Flow Crunch

How (and why) the flow of cash in construction slowly strangles some of its most critical companies.

John owns a small construction company and has for some time. He’s spent an entire career in the business and is proud to run a company. Today, not unlike many other days before, he finds himself in a tough spot. He needs cash and doesn’t have it.

His workers and vendors need to be paid or they’ll stop work, but he hasn’t been paid for the work they’ve already done. He doesn’t have the cash on hand to pay them. Making matters worse, he’s contractually obligated to continue working - which means they need to keep working or his situation gets worse.

John’s options are limited and available options aren’t great.

In the long run, he can place a Mechanic’s Lien on the property and force the conversation about payment. This takes time and money he doesn’t have now.

In the short run, he has a few options, none of them particularly good. They range from using a credit card (assuming his isn’t maxed out), drawing on his personal savings, or drawing from retirement savings. In a perfect situation, he’d have a line of credit for exactly this scenario - but fewer than half of companies like his do.

Like many others he chooses to stay alive, but it’s not without risks.

He took the hit on retirement savings penalties and put more personal money into the business to keep things moving. He views it as an investment in the long term. It’s not ideal, but it will pay off one day he hopes.

What do situations like this mean for John and construction as a whole?

We focus on John’s situation today because where he sits in the flow of cash makes his life particularly hard with implications for the broader value chain. Companies like his bear most of the capital burdens of the project and they tend to be the least well positioned to do it.

There are three important implications of consistent cash flow struggles:

It makes it hard to focus on running a good business and managing projects well. When cash flow is a struggle, he spends most of his time chasing payment, keeping his vendors up to date on when they’ll be paid, and finding ways to bridge to the next payment.

It makes it hard to grow his business. Taking on a new project means exposing his business to significantly more risk of running out of cash or damaging his existing relationships with clients, vendors, and workers. If it endures for long, he goes out of business (and there go those retirement funds he put in to keep the lights on.) It’s scary to sign up for this and can be hard to convince clients to let you do it.

It puts the project as a whole at risk. John’s company is critical to keeping the overall project on-time. If he falters, it ripples through the entire project. This might be because his vendors cease to work, but it may be because he doesn’t have the time to effectively manage the project and something gets missed. There is insurance in the project to offset the costs of these issue, but it doesn’t resolve the delay.

John’s not a real person, but his story is real. It’s one experienced by many of the people responsible for the built environment we often take for granted. Construction companies have the highest rate of failure for new companies and this has a lot to do with it. Profit margins in construction are slim, but even profitable businesses die when they run out of cash.

How did this happen?

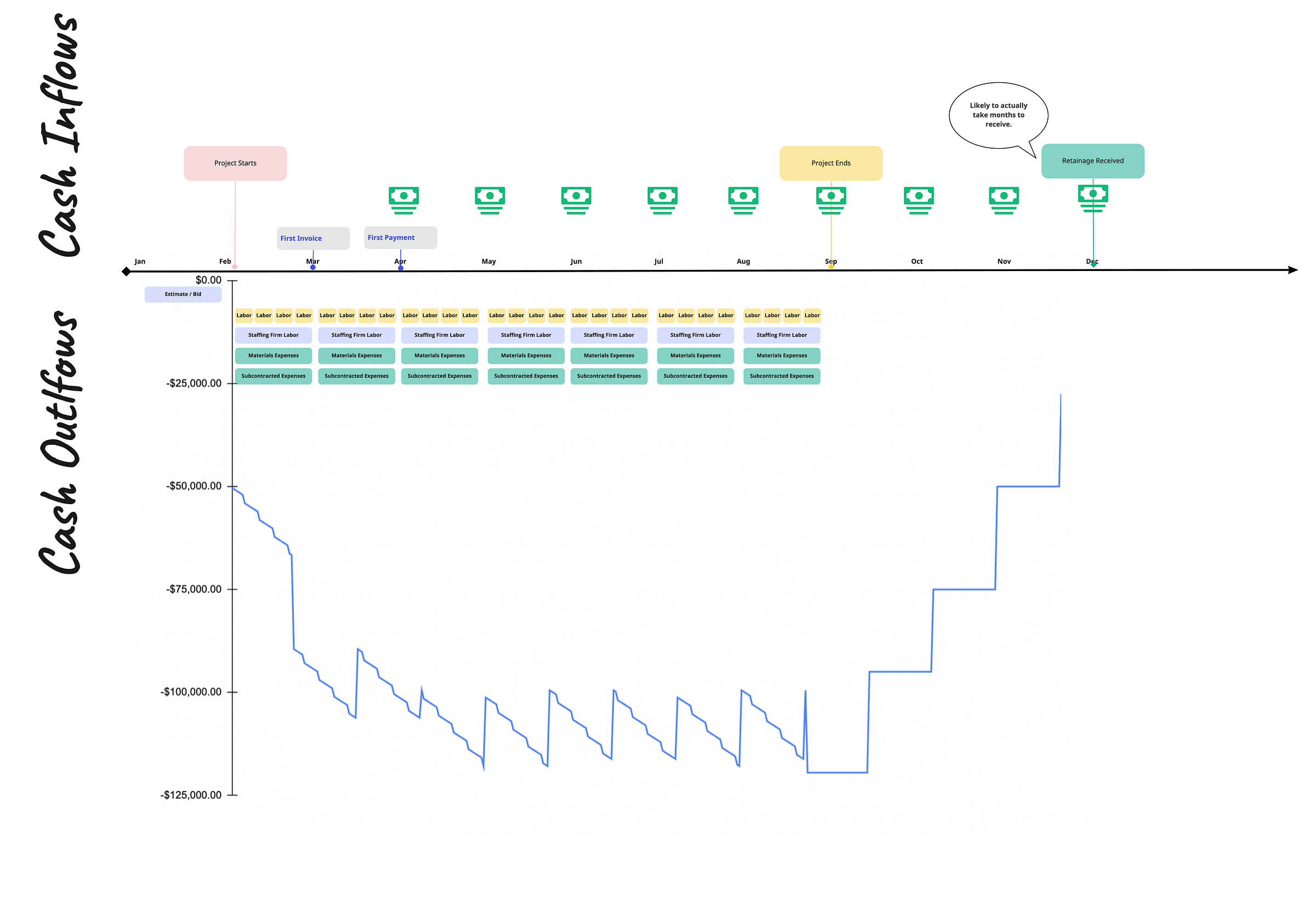

To understand how this happened, we’ll need to understand the flow of cash. First let’s look at an example of what John’s cash flows might have looked like on this particular project.

He starts off behind because he has costs associated with winning the project - then at the completion of his work he still likely has months to wait before he’s paid the retainage (5-10% withheld from every invoice.) Retainage typically represents most, if not all, of the profits he might’ve planned for. It’s a big issue.

For a project where he’s billing $50K/month for 9 months, he’ll need to be prepared for over $100K negative cash flow for most of the life of the project - assuming everything goes right. Multiply this by a number of projects, a late payment here, a missed payment there and you begin to see how things get tricky for John (often.)

John’s situation results from a structural problem. He gets paid for work slowly, his expenses accrue quickly.

So, let’s look at how this happened. Here’s a map of how payments flow in the ideal scenario - sometimes payments to subcontractors can take far longer.

In the vast majority of large projects, the following parties are involved:

Owner - this is the person or company who wants something built and plans to own, operate, or sell it at the conclusion of construction.

General Contractor - this is the person or company hired to manage and coordinate construction. They typically don’t do the work, they bring together the right people at the right time to get it done.

Subcontractors - this is where the work happens. These companies own the delivery of specific components of a project (think concrete, electrical, etc.)

Materials Providers - this is a company that, not surprisingly, sells the necessary materials required for the work.

Staffing Firms - this is a company that provides temporary labor, something heavily utilized in places without labor unions.

Workers - the direct employees of the subcontractor.

The companies least able to bear the burden of slow payment are the ones most often forced to do so.

Here’s the rub. Generally, as you go lower down the chain you’re dealing with companies and individuals who have less and less cash on hand, which means they need to be paid more quickly in order to stay afloat. Conversely, as you go up the chain you’re dealing with companies and individuals who desire to pay more slowly (and have the leverage to negotiate for it, because they have the work.)

John is caught in the middle. His client (the GC) can slow pay him, especially when they’re paid slowly by their client (the Owner) – it’s in the contract. However, John needs to pay his workers weekly (or they’ll go somewhere else), his materials suppliers monthly (or they’ll stop sending materials), and some of his subcontractors even when he hasn’t been paid (or they’ll go out of business/cease working.)

Here’s an overlay of John’s cashflows - here we assume they’re getting paid every 30 days, which is the best case scenario. They start the project off behind because they have costs associated with estimating and bidding to win the project.

A few thoughts on why it works this way.

Based on my reading and conversations, there are a few reasons we might’ve ended up here. At the top of the value chain, Owners and GCs are incentivized to hold onto cash as leverage to enforce performance and because having more cash is better than less cash, all things being equal. They can get away with this because they have leverage at the outset of the relationship, tend to be more sophisticated, and because “it’s just the way things are done.”

The two primary incentives for a policy like this one are:

Performance - it’s much more challenging to take back money than it is to withhold it in the first place. In general, the longer you withhold payment the more time you have to discover something wasn’t performed correctly and use non-payment as leverage. This also keeps people incentivized to finish the project.

Float - it’s an old concept and it’s simple. Money has value, so the more you have the better off you are for a variety of reasons. In general, the longer you can wait between getting paid by your customer and paying your vendors the better off you are.

The enabling factors that lead to it:

Power dynamics - who has the demand? For the Owner - they’re the client and they can dictate the terms. For the General Contractor, they’ve won the project and they can dictate the terms. The terms cascade until they can’t anymore because someone won’t deliver without payment (workers and materials providers.) This is exacerbated by companies further up the chain tending to be larger companies with more leverage, even beyond that engendered by their place in the chain.

Sophistication - further up the value chain, you tend to see larger companies. They have legal teams. They have finance teams. They have teams dedicated to reviewing the details. For John, he’s “the guy” - so while he’s negotiating one contract, he’s chasing payment for another, estimating another, and operating his business too.

Perpetuating the Status Quo - to some degree I think this is a situation where everyone’s come to accept, “it just works this way.” I think this is equally attributable to the more dominant parties being the beneficiaries and the fact change across a complex value chain is hard.

Finally, there appears to be an emerging trend of more adversarial dynamics within projects. The more conversations I have the more I hear how there’s been a shift from cooperation to competition on a project. Within the context of a single project, there’s a desire to shift as much risk down the value chain as possible. This seems to be getting worse, not better.

It’s bad, especially for John, but not all bad.

Companies like John’s are often operating on a knife’s edge. They’re a few mishaps away from going out of business and spend too much of their time focused on getting paid to give their company and the projects they run their full attention. It’s not great for them and it’s not great for the value chain as a whole. However, things are changing. It’s not happening fast enough for company’s like John’s, but the world is moving in a positive direction on this front.

Two bright spots in particular come to mind for me:

GCs are beginning to understand the implications and trying to help. Turner Construction is proving itself as an industry leader by giving their trade partners an option for early payment. As an Entrepreneur in Residence, working with Turner, I’ve seen them take a one-of-a-kind stance to improve the plight of subcontractors with their Advanced Payment Program - offering their trade partners access to early payment options that can help someone like John avoid dipping into their retirement to keep going. I expect to see more of this as we move forward, particularly in the current economic environment.

Legislation is improving around prompt payment. It’s been enacted in most states, meaning there’s a push to reduce the incentive for extended payment terms. In general, this typically means companies can only wait 15 days after they receive payment to pay their vendors. However, it seems enforcement has been a challenge and visibility into when payments were received (thus starting the clock) is not always clear. Technology like Oracle’s Textura is helping create more visibility and improve enforceability, at least with the largest companies.

Source: Levelset Prompt Payment Guide

In the next newsletter, we’ll take a look at how information flows up and down the value chain creating challenges and opportunities for the proper distribution of cash, risk, and the successful delivery of projects.