The Construction Value Chain - Part I : Why so messy?

How our drive for bigger, more comfortable buildings is probably the crux of complexity in construction.

Construction is messy. Period.

Wrapping your head around construction is tough. It’s a big, complex, and complicated ecosystem. A former colleague once described a situation as being “like an onion. Except when you peel a layer back, it grows.” Construction can feel this way. When I understand one level of zoom, then go in for further inspection, I’m often surprised to find it functions far differently than my intuition suggested.

I’m a big believer in Richard Rumelt’s notion of the Kernel of Good Strategy, specifically the importance of a proper diagnosis. The diagnosis is about understanding the dynamics of what’s happening in the world and distilling that complex reality into a representation that’s both powerful (this is the source of critical insights) and easily understood (you rarely execute a strategy alone.) Diagnosing the situation is where most strategies fail in my experience, which is to stay most of the time there was never really a strategy.

Returning to construction this means there’s no viable path around building a mental map of this complex ecosystem, unless I plan to waste my time (hint: I don’t.) A primary goal of this newsletter is helping clarify my thinking and the corresponding map.

So, my question became: where to start?

The answer: the beginning (sort of.)

What I mean is I think it’s helpful to understand where construction started, where it is, and what led it to evolve the way it has.

Before we dig in, let’s limit the scope of this exploration. We’ll define construction as: The process of designing, building, and maintaining the structures we live, work, and play in.

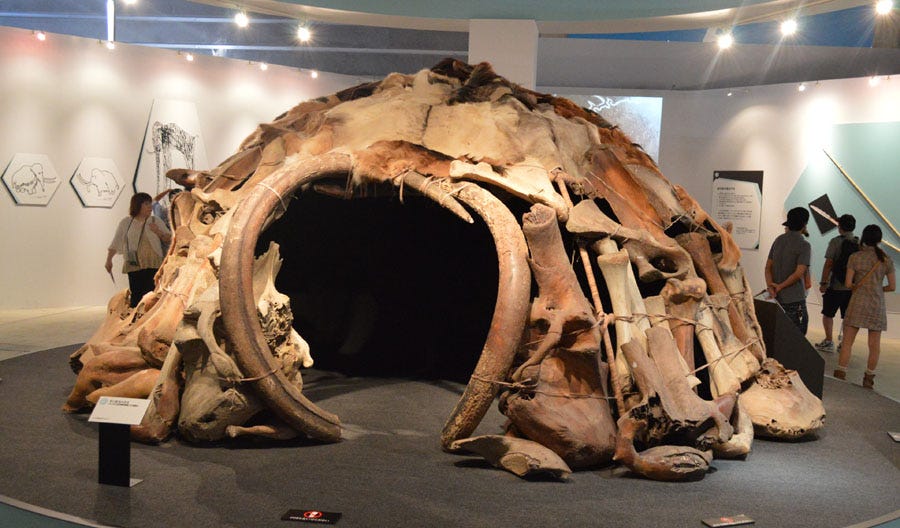

Looking to the extremes to help tease apart important rules and mechanisms: Mammoth Huts vs. Skyscrapers

The first human “construction” was almost certainly a hut. There’s evidence to suggest humans were making tents as early as 40,000 BC. Primary building materials? Mammoth remains.

At the time this would’ve been the most relevant structure in the lives of people who had one. In the quest to better understand construction as an industry, I think it’s helpful to reflect on a few themes of this early construction:

The design was simple. Once you had the idea outlined for you, it probably was pretty easy to replicate. There was a process, to be sure, but one we could all probably learn quickly. (We’ll set aside the requirement of bringing down the Mammoth first.)

The scale was small. These structures would’ve only been intended for a few people and would’ve needed to be portable, consequently I’m speculating a single family could likely build this on their own. Further, the strain on most of the materials would’ve been far below their capacity..

The stakes were low. If the structure failed, someone got wet or had to dig out from under a mammoth skin. No fun, to be sure, but probably no worse than most of us have experienced on a standard camping trip. Also, what was your next best alternative? If necessary, you were going to eat the risk.

So, the hard part was killing the Mammoth (see, getting materials has always been hard.) After that, presumably any person was on effectively level footing to build the finest structure known to man.

Contrast that structure with Burj Khalifa, completed about 42,000 years after that first tent. At a bit over half a mile high, it supplies around 250K gallon of water per day to occupants, contains 57 elevators, and takes a team of 36 window washers more than three months to clean the entire building (they’re spared the top 27 stories by an unmanned cleaning system that cost $8MM.)

If we review some similar themes, we see (not surprisingly) a very different picture:

The design was incredibly complex. No one person could design this on their own. It’s the design of a complex, interdependent system where thousands of tradeoffs were made around what materials exist, what materials are available, what materials are cost effective, and how do the inherent properties (weight, strength, etc.) support the overall design. It rests on thousands of years of learned best practices combined with thousands of simulations to identify scenarios where it might fail.

The scale was massive. No one company, much less person, could build this alone. Thousands of people, hundreds of companies, years of planning, years of effort. One person wouldn’t have been able to install the revolving doors at one of the entrances. Large-scale coordination was critical.

The stakes were high. If the structure fails materially, in a best case scenario it’s very expensive in a worst case scenario there’s significant loss of life. Add to this the fact that big buildings must account for the fact that they draw attention (part of the idea), but sometimes from people with plans that run contrary to the designers intent. The World Trade Center was not only attacked on 9/11, but also bombed in 1993.

Now, let’s use this contrast to tease apart some of the reasons construction is so complex and messy.

Complexity increases with specialization, which ultimately drives coordination costs up (assuming fragmentation.)

The curve of complexity would’ve taken off with the agricultural revolution - more people were deciding to hang out together and could afford to specialize.

The subsequent increase in density naturally leads to specialization. Then, specialization tends to beget more specialization. Making use of specialization, typically increases complexity. The two of these together lead to increasing coordination costs, especially in a fragmented value chain like construction.

My takeaway is this: After civilization sparked specialization, complexity was driven by ever increasing desires for bigger, more comfortable buildings (or human nature.)

To achieve the improvements in scale and comfort we sought we needed to massively upgrade and diversify our materials / technology, which leads to upgrades in our tools, which leads to specialization.

A few things struck me as I went through this thought exercise:

Specialization happened in two thematic areas I hadn’t viewed as separate before. Size vs. Comfort.

Specialization intended to build bigger, better structures. Think concrete, steel, and the new designs patterns they enabled.

Specialization that happened around improving the lived experience of a structure (think electricity, running water, air conditioning, etc.) This is a whole new vector that only showed up relatively recently.

The rate of specialization seems to be very material/technology centric. The evolution of specialization seems to track effectively 1:1:1 as (material / technology : tools : skills). Each time there’s a big change here, we see a fork in the tree of specialization. This makes perfect sense upon reflection, but wasn’t something I’d considered.

Construction has tended to avoid major consolidation (i.e. it’s really fragmented) for a few reasons :

Buildings are distributed geographically and they’re big, making centralizing work hard because you never build in the same place twice and expensive because transporting big stuff is costly.

Barriers to entry are low - most companies doing the work don’t need massive upfront capital to get started or be as productive as larger companies. At least they haven’t historically.

Regulations/codes are typically applied at the local level (i.e., it’s hard to know all of the rules, much less guarantee you play by them.)

Specialization ultimately took another fork, at a different level, to minimize coordination costs and increase productivity by working on more of the same type and scale of project. Think Commercial vs. Residential. I attribute the clustering here as largely being driven by scale, which is the biggest influencer on the materials/technologies in use as well as the regulatory environment (remember there’s more at stake.)

Wrapping Up

In summary, it’s so complicated and messy because we’ve been really successful in pushing the boundaries of scale and improving the livability of our structures. That success has been predicated on specialization, but the world to-date hasn’t been amenable to centralization. This leads to fragmentation. This fragmentation means coordinating costs can be quite high and the overall picture can be quite messy. I find myself thinking:

Maybe the mess is a feature, not a bug.

Maybe there are applicable lessons from industries, businesses, and products that have embraced the mess vs. trying to wrangle it.

Maybe not.. maybe the mess is an artifact of how we once did it and will be wrangled by consolidation and moves to modular design and a more manufacturing-like assembly process.

In Part II, I’ll take a shot at answering some of these questions through a deep dive into Commercial Construction. In particular with an eye toward understanding the flows of information, cash, and risk (effectively the Central Nervous System of construction) through this complex ecosystem.

I’m not an expert. If you are, I’d love to talk - especially if you think I got something wrong!